The Texas Hill Country, recognized around the world for its natural beauty, hosts a wealth of environmental, cultural, and economic resources within its 18,000 square miles. The Edwards Plateau, Llano Uplift, and Balcones Escarpment are defining geologic features that serve as the foundation for the diversity of vistas and peaks, valleys and streams, plants and animals—an ideal setting for habitation and recreation by those who enjoy nature. Unfortunately, these unique natural resources are now endangered by the aggressive expansion of aggregate mining companies proposing numerous rock quarries and cement plants throughout the region.

Encompassing a 17-county area, the Hill Country is located just to the north and west of fast-growing San Antonio, Austin, and the rapidly urbanizing Interstate Highway 35 corridor connecting these cities. The Hill Country provides water and offers an array of outdoor recreational activities to many of the 4.5 million residents living in this region. An increasing number of residents now reside in the Hill Country, enjoying the high quality of life and relaxed country living. It’s a magnificent place to raise a family or enjoy retirement surrounded by natural serenity.

While this region is admired and prized for its natural beauty, many unincorporated areas of the Hill Country are now in the crosshairs of corporations setting up rock quarries and cement plants. The aggregate industry and their shell companies now own over 25,000 acres in Comal County (seven percent of the entire county land area). Most recently, Alabama-based Vulcan Construction Materials has submitted a permit application to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) to convert the former White Ranch, a 1500-acre parcel of pristine ranch land between Bulverde and New Braunfels, into a limestone quarry and rock crushing plant. Instead of being planned for a more appropriate industrial zone, Vulcan is proposing to helicopter a quarry into a rapidly growing residential area that to date encompasses 6,000 properties and 12,000 residents within a five-mile radius. Families have built homes, established gardens, and are raising their children or enjoying retirement in the tranquility and beauty of Comal County.

Limestone is a natural asset of the Texas Hill Country. It is attractive not only for its geological formations such as bluffs, outcroppings, canyons, and caves, but also as a building material for the construction industry. At first glance, this seems like a perfect recipe for growth in the region. But when mined and processed carelessly, or near residential areas, limestone quarrying risks loss of habitat for native flora and fauna, demands high volumes of water, produces large amounts of pollution, and negatively affects human health.

Limestone is a commodity for aggregate companies and they are purchasing, at top dollar, large tracts of agricultural and ranch land to take advantage of the extremely profitable aggregate demand not only in this area but all around the state. The aggregate industries acquisition of private ranch lands and the development of these lands leads to incompatible land use (e.g., quarrying directly atop the Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone). The process that TCEQ employs to issue air quality permits to these very same companies is heavily appropriated to “guarantee” awarding the permit, despite the incompatible land use. Public outcry, scientific evidence contradicting the alleged protections offered by the aggregate industry and the testament to cascading injurious events such as fugitive silica dust affecting residents’ health, over pumping of water leading to dry wells, groundwater pollution, noise and light pollution, habitat destruction, and property devaluation all are inconsequential to the permit process.

Currently, six federally listed endangered species occur in Comal County, including the golden-cheeked warbler, whooping crane, two aquatic insects, a crustacean, and a fish. In addition to habitat destruction, the potential for polluted water runoff could adversely affect area wildlife. Because of the unique karst hydrogeology characteristic of the area, pollutants can travel quickly through the aquifer and contaminate springs and rivers in a very short period of time—sometimes in a matter of hours—poisoning fauna dependent on these water sources.

The Edwards Aquifer is one of the most prolific artesian aquifers in the world, serving the diverse agricultural, industrial, recreational, and domestic needs of almost two million people living in a band from southwest of Austin through New Braunfels, San Antonio, and west to Uvalde. The Edwards Aquifer is the only aquifer in the State of Texas designated as a “sole source” aquifer. In fact, the Edwards Aquifer is the only aquifer in the state of Texas to have its own statute in the Texas Administrative Code (TAC), emphasizing the importance of protecting the Edwards Aquifer and hydrologically connected surface streams from pollution. Over 90 percent of this water flows (often underground) through Comal County. Since the proposed quarry site is in the Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone, a high potential exists for water contamination from silt, oils, chemicals, and hazardous waste from the mining process.

For aggregate mining, the primary way of suppressing dust is water. Unfortunately, when an aggregate company seeks an air quality permit from TCEQ, there is no requirement to prove that there is sufficient water nor that the amount of water pumped out will not harm the quality or availability of water for residents, many of whom are using aquifer water to support their livelihood in agriculture or ranching.

To understand the volume of water being used in an aggregate mining operation, see this comparison chart below:

4-person single house dwelling: 146,003 gallons/year

800 ton-per-hour crusher*: 280,320,000 gallons/year

*This water usage excludes water necessary to suppress dust on conveyor belts, stock piles, internal quarry roads, trucks, etc.

Water resources in this area are taxed. In Bexar County (San Antonio), the Edwards Aquifer water supply is being supplemented from a variety of alternative sources to accommodate the increasing demand on their water resources. Water providers are pulling from Medina River in the west, built a desalinization plant to the south, are leasing two wells from the Trinity to the north, purchased water rights in Carrizo Springs, and are spending millions on a 142-mile pipeline from a Burleson County aquifer. Comal County and surrounding areas are already in Stage 2 water restrictions and Canyon Lake Water Service Company turned off the taps recently to a residential subdivision due to low water storage levels.

Quarries can no longer drill into the Edwards Aquifer, but now must drill deeper into alternative aquifers like the Trinity. Neither aquifer can replenish its supply fast enough to meet current demand. It is unfathomable that TCEQ does not require the aggregate industry to ensure that there is sufficient water supply to ensure proper dust suppression as well as ensure that their water use does not lead to over-pumping thus affecting local landowners’ water availability. To say that one land owner’s private property rights overrides the perils it causes to a multitude of other property owners is shortsighted and outright wrong.

In addition to these negative effects on wildlife and water, the aggregate industries most notable impact will be on human quality of life. On the surface, a quarry may seem to be a mere nuisance owing to the noise, heavy traffic, and powdery white dust that can be seen settling everywhere. However, in addition to the visible dust, limestone quarrying produces invisible microscopic particles of minerals, including calcium, magnesium and silica, which are easily airborne, and carried for long distances on the lightest breeze. The microscopic silica particles pose significant health risks for those exposed to them via inhalation, or contact on delicate exposed tissues of the eye, nose, and upper respiratory tract. Specific health risks of silica dust exposure include silicosis, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary tuberculosis and rheumatoid arthritis.

There is unbridled permitting going on in Texas by TCEQ. TCEQ has granted over 8,000 air quality permits between 2015 and 2017. Not all are related to the aggregate industry. Regardless, in the last ten years the aggregate industry has chipped away at the TAC rules making it easier for industry to meet requirements to obtain air permits. They have been eliminating citizen’s opportunities to protest/contest aggregate operations, are eradicating the opportunity for contested case hearings for certain permits, and are drastically reducing the time frames with which to respond to public meetings or public hearings.

TAC rules related to aggregate air permits are deficient. They are not required to utilize the latest technologically advanced applications and processes available to industry and they do not address current Best Management Practices. Once granted, TCEQ only performs onsite quarry operation audits every three years. Between onsite audits, TCEQ relies solely on complaints from local citizens or the plant operators self-reporting documentation. Also, the industry is allowed to self-audit under the Texas Environmental, Health and Safety Audit Privilege Act. Aggregate industry operators monitoring their own air quality and self-auditing is comparable to the fox guarding the hen house!

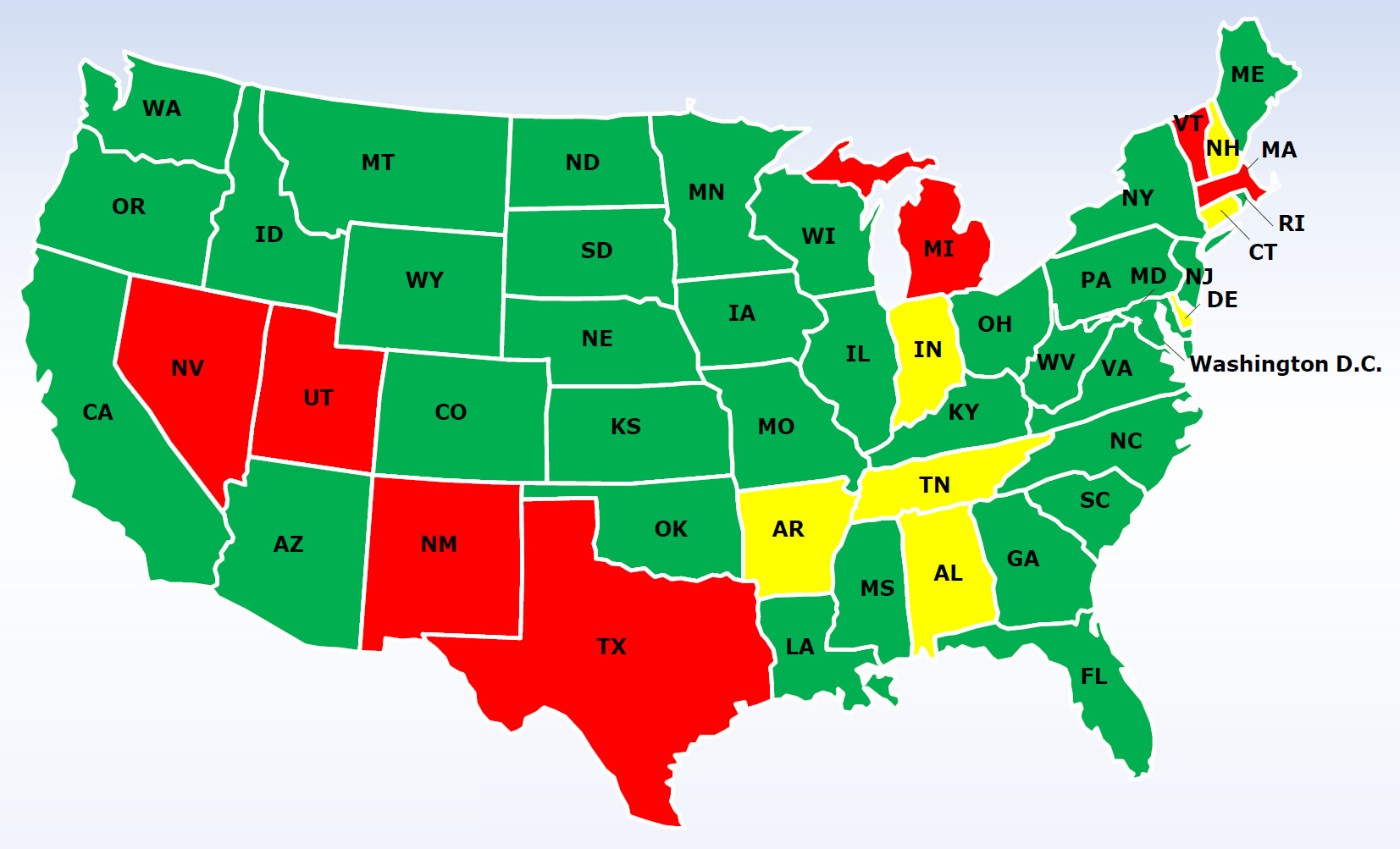

Finally, there is data that shows that the aggregate industry in Texas is not as stringently regulated as other “open pit mining” industries in Texas. Aggregate mining regulation in Texas doesn’t even compare to aggregate mining regulations in other states. Due to this lack of regulation the citizens affected by the prolific, irresponsible aggregate industry are left with no other options but to protect themselves and their properties by filing expensive nuisance lawsuits against these plant operators.

Imagine this: you are on an outing to enjoy a weekend on Canyon Lake or canoe the Guadalupe River. Your journey takes you on Texas Highway 46 or FM 3009. In route to your scenic destination, you encounter numerous heavy trucks emitting pollutants and bellows of fugitive dust. Then you pass a huge, unsightly hole in the ground with massive equipment making unbearable noise and spewing carcinogenic dust into the air. The peace, serenity, tranquility and beauty you came to enjoy will be gone. Welcome to the new “picturesque” gateway to the Texas Hill Country.

Thankfully residents of the area are not going down without a fight. Neighbors have banded together to form grassroots organizations like Stop 3009 Vulcan Quarry, Texas Environmental Protection Coalition, and Boerne to Bergheim Coalition for a Clean Environment. These citizen-driven groups face an uphill fight against the well-heeled aggregate industry, TCEQ, the Texas Aggregates and Cement Association (TACA), and politicians opposed to common-sense zoning and land use restrictions. In Comal County, it will likely be months or years before an outcome is known.

Related News

Quarries Pose a Risk to Local Caves, Water

September 19, 2019

Landowners discover new chamber in Double Decker Cave, in Comal County, Texas between proposed Vulcan quarry site and Natural Bridge Caverns.

Love Your Honey, Love Your Hill Country Dinner & Auction

March 29, 2019

March 29, 2019: Celebrate your love for your honey and Hill Country! Inaugural fundraising dinner and auction at Castle Avalon. Great food, libations, music, silent and live auctions.

Get the T-Shirt

December 1, 2017

Publicly show your support for protecting the Hill Country and defending our families with a t-shirt! Available for $15 in S, M, L, XL sizes.